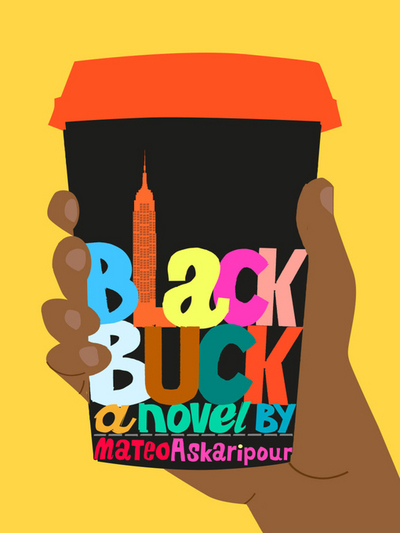

The self-help guide to leading a workplace revolution.

“Reader: By this point, you should know that nothing in life is free, especially freedom.”

This part pseudo-sales manual, part workplace satire was everything I hated (read: loved, for those who can’t speak sarcasm) and needed while drowning in a sea of performative allyship everywhere I look.

What happens when you walk into the room, your first day on the job, and notice that you are the diversity hire? You push the thought aside, thinking no, that’s ridiculous, until you are being grilled every day for not being as up-to-snuff as your fellow white hires. You discover that the two people who started the same week as you had some sort of advantage—they were an up-and-coming football player who was scouted by the NFL, or their daddy had intergenerational wealth to his name and an even bigger network of connections to get you through your first week in sales. Where does that leave you, the one who was spotted for merit, for potential, who sold the CEO himself on a coffee he didn’t want in a lobby-bound Starbucks?

/

According to its page on Wikipedia, the term “Black Buck” was used as a racial slur in the American post-Reconstruction era to describe Black men who defied the will of white men and were considered to be “largely destructive to American society.” Among other pretty offensive and racist definitions, the term “Black Buck” was overall a derogatory racial slur, and was co-opted into propagandic white supremacist media such as Birth of a Nation to present the white American people with their own fears of what Black men were capable of.

I had only learned about this term after I had read Askaripour’s novel and discussed it with a close friend of mine, who brought up the term’s grotesque historical meaning. Now, I can see Askaripour’s novel with a new layer of clarity (read: sociohistorical context that only comes to light when all histories are shared), and with a renewed sense of empowerment. Here, Buck (formerly known as Darren Vender) takes the slur that was forced upon him by his white supervisor—and ultimately by the white men who for centuries have controlled the means of social representation—and reclaims its as a term of empowerment. In this contemporary moment, “Black Buck” has now come to mean a person of color who stands as a leader of revolutionary defiance against the white American will, whose aim is to tip the scales of the capitalist system in favor of people of color, at last.

/

(White) people always get upset with me when I use the term “white supremacy” in conversations about workplace inequality, and it’s frustrating to navigate those conversations and make some sort of progress without knowing the meaning behind the terms we use. So let me take a moment to define what I mean when I use the term “white supremacy” here. No, I am not talking about tiki torch-bearing Proud Boys or the white hoods that we attribute to white soup (my shorthand; I’m tired of seeing this word in my own writing). I’m talking about the systemic privilege inherent in white people’s success: in being heard, in being uplifted, in being influential, in earning a living wage, in attending a well-funded school, in receiving mentorship, in having doors opened for them. So when I say a certain working environment enables a white supremacist structure, I’m saying that environment maintains a well-established hierarchy of white people at the top determining the business model and profitability of the people they oversee below—and those people below them are more often than not people of color who are drained and tired of how the system siphons their potential for success, longevity, recognition, and advancement.

On the surface, Black Buck is all about race—here we see firsthand how the Western corporate world operates on the same system of white supremacy that upheld an empire of slavery and inequality. Buck also tries to convince white readers and salespeople that it’s more than about race—it’s about privilege. It’s about the advantages given to some over others, which convinces hiring boards and college admissions that “x people just aren’t skilled enough” to make the cut. It just so happens that, more often than not, the white people are the ones who have the head start, the extra prep time, the connections from higher up to make sure the staff room every Thursday morning is full of people who don’t look like you.

So, what does someone like Buck do when facing a sea of white sharks, some of whom want to be his friend, some who want him out? Break down the pipeline of white supremacy (ahem, “privilege,” if you’re still up in arms) from the inside, that’s what.

Yet another aspect of Black Buck that rings painfully true to our workplace reality is that we can’t simply flood the system by bringing in more of the underprivileged, the disenfranchised, into the places they have been barred from, because the system will fight back. It’s one thing to bring D&I initiatives to the white workplace and expect that 3-hour training workshop will solve all your problems, but it’s something much more realized to bring people and (the infamous “yes, and…”) establish a support system for when the system built around the job itself turns against you. Because trust me—or your new sales pep-talk buddy, Buck—it will. In this “self-help” book that provides snippets of guidance on the art of the sale alongside personal narrative, Buck teaches us all about how we can build a flourishing system that works against the ones that fail people of color.

Mateo Askaripour masters the writerly duality of observing both internal conflict and external detail. He has also created a romp of a story the likes of Sorry to Bother You—this novel is packed with action, smart quips, and blatant depictions of racism in the workplace meant to both jolt the reader and numb us to the persistence of oppression. It’s no wonder Askaripour snagged a TV series deal with Black Buck—he has the prowess of a screenwriter who settled for 400 pages of prose. He has managed to make a workplace novel a thrilling, caffeinated ride. And that’s as it should be—I’m only half-Asian, but I can certainly attest to a lifetime of never-ending panic. I have only ever understood my relationship to work as fearful, and that’s because we have been told to be constantly afraid of losing our jobs if we’re not good enough, or not as good as that white coworker next door. This applies not just to publishing, but to sales and whatever other cubicle world exists outside my realm of knowledge (and also, retail. Come on, that world is another ring of white supremacist hell entirely).

What’s (not) shocking about this book is how close it veers to real-life discussions (or rather, abandoned discussions) around diversity and inclusion in the workplace. I felt that gut punch every time someone in this novel attempted to steer whole conversations away from race, every time that white hiring manager or white reporter suggested we not use the overplayed “race card” when confronting bias, every time a white coworker or team leader expressed concern that the minority was either not pulling their weight or outshining everyone else, never leaving enough room for a person to just be. We are always selling ourselves in the marketplace of whiteness, either on our work ethic or our presentability or our coherence when using a sterilized English that dances and skirts around the heart of the matter. No one wants to be direct when confronting their whiteness. Ditto acts of workplace inequality. But, in creating an office space where the marginalized are invited to come as they are, Buck reframes the identity of the workplace persona in a world where there isn’t a white manager around to keep an eye on you. You’re doing just fine on your own. Better, I hope.

To all the Happy Campers out there, reading this review or the book itself: here’s to breathing. Here’s to being.